Your Ultimate Guide to Ocular Histology in 5 Steps

Ocular pathology is a broad discipline that not only involves diagnostic or post-mortem evaluations; Ocular histology is more frequently requested during in vivo preclinical testing as a method of predicting potential clinical adversities. Within a translational good laboratory practice (GLP) environment, it remains crucial that the pathologist not only feels comfortable to diagnose the ocular lesion but also be able to locate each one of them. Best practices recommend that the pathologist must have access to the standard operating procedures (SOPs) from each step in the study design. This involves the route of exposure, clinical ophthalmic findings, necropsy observations, and histology procedures. Ocular treatment-related findings need to be differentiated from common artifacts, spontaneous changes, and iatrogenic findings, so histology sections of good quality with proper orientation and minimal tissue artifacts are essential.

Please find hereby my top 5 guide list which will help each ocular histologist and pathologist to achieve excellence:

1. Be Nice at Necropsy: Treat the ocular globe as it was still alive! Remove carefully the full globe with smooth traction and dissection in order to prevent autolysis of the retina. Always identify the right/left globe and mark the original location(s) such as superior-inferior and nasal-temporal with indelible ink in order to avoid loss of orientation during embedding and trimming.

Do not incise the globe at necropsy!

2. Be Quick at Fixation: Place the globe in fixative as soon as possible. The container should be wide mouthed; smaller specimens such as adnexa or optic nerve should be placed in a mesh cassette before putting inside the same container. Samples should ideally be fixed in greater than or equal to 10 times the sample’s volume. Various fixatives such as formalin, or modified Davidson’s solutions can be used. If sample shipping occurs with third parties during winter months, it is recommended to add isopropyl alcohol to the formalin in a 1:10 ratio to prevent freezing artifacts.

Do not inject any fixative into the globe!

3. Be Delicate and Consistent at Histology: Ocular tissues are easily distorted and damaged if not handled correctly during histology procedures.

3.1. Trimming - Processing techniques should be written in function of the laboratory animal species and specific study design. It’s always beneficial to locate the dorsal portion of each globe and make 2 sharp incisions (lateral and medial) that produces a small window parallel to the optic nerve. Paraffin sections are the gold standard. However, tissue processing remains a critical step. Ocular globes should ideally be processed with a customized processing program and be treated separately from routine organs because they are sensitive to dehydration and prone to artifacts such as cleft formations in the cornea or retinal cracks with detachments. These common artifacts interfere with major ocular diagnosis such as edema or real retinal detachments and they may invalid the study.

3.2. Embedding should continue to be standardized without loss of orientation. Depending on study design, one single slide or multiple serial sections can be taken. Each individual eye section should be place with the same uniform orientation on each slide.

3.3. The Hematoxylin Eosin (HE) staining protocol is widely accepted in routine studies. Additional stains include Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) in order to detail specific eye structures such as the lens capsule and the Descemet membrane.

It is absolutely forbidden to take out the lens during histology procedures for technical reasons!

4. Know your Anatomy: Eyes do show anatomic specificities depending on the laboratory animal species. Therefore, awareness about these macroscopic and microscopic anatomic specificities will help you to achieve your histology targets.

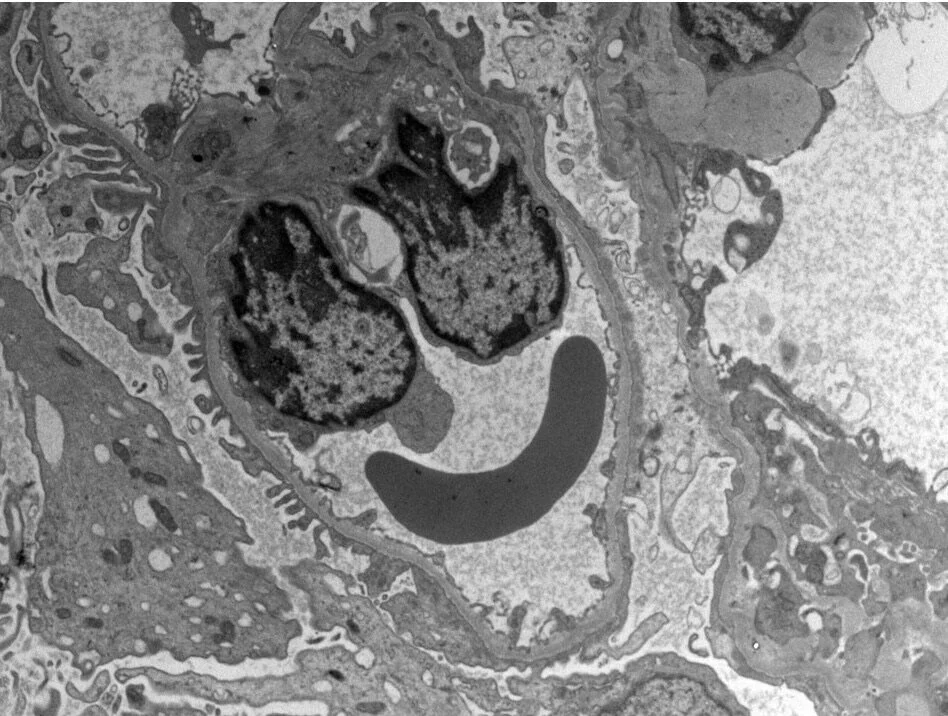

a. As a macroscopic example: the ciliary artery in rats is visible at gross inspection and is located inferior to the optic nerve. This small vascular structure will help you to confirm the orientate the globe.

b. As a microscopic example: human primates are the only laboratory animal species to possess a fovea which is the equivalent of the fovea centralis in humans. The fovea is responsible for the sharp central visions also called foveal vision. Therefore, it’s often mandatory to have the fovea present at least in one of the slides for further histopathological evaluations. Advanced skills are needed during the cutting stage in order to locate the fovea.

5. Act as an Ocular Team: Ocular histology is often the bottle neck when designing an ocular study. It’s mainly the route of administration that will guide you through all histology procedures. These routes are ranging from topical or systemic applications, to intravitreal, and subretinal injections are common experimental procedures. In many ocular studies, one eye is treated and the other is left untreated or acts as sham. Necropsy observations are usually minimal, but in vivo imaging technics, such as Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) are highly valuable for future macro-micro correlations. Therefore, it’s always preferable to ask for details before starting your histology.

It’s absolutely a no-go performing ocular histology tasks within a blind matter.

Ocular drug research is a quick evolving field: the various study designs will challenge your routine laboratory workflow. In addition, animal models for specific ocular diseases (e.g. age-related macular degeneration) will need extra inter disciplinary collaborations with extra histology expertise. Finally, various medical devices are used in ocular protocols. Your histology approach should be focused to maintain the medical device within its original background and not to harm the interface

As an ocular pathologist, I really advise you to work as an ocular team. Develop your expertise over time and plan your advancements carefully. It all starts with awareness that eyes are different. You only can deliver perfection if the whole ocular chain has been well documented. When you need to implement a new histology technique, I advise you to run pilot studies first in order to feel comfortable!